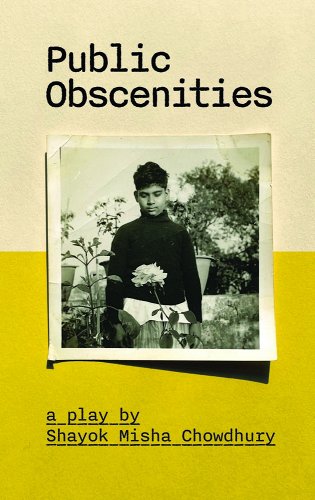

Shayok Misha Chowdhury is an Obie Award-winning writer and director. His playwriting debut, Public Obscenities (Soho Rep, NAATCO, Woolly Mammoth, Theatre for a New Audience) was a New York Times Critic’s Pick and named in The New Yorker’s Best Theatre of 2023. Misha is the recipient of a Princess Grace Award, the Mark O’Donnell Prize, a Jonathan Larson Grant, and the Relentless Award for his musical How the White Girl Got Her Spots and Other 90s Trivia. Other favorite projects include MukhAgni, a performance memoir, and Englandbashi, a short experimental film. A Sundance, Fulbright, and Kundiman Fellow, Misha’s poetry has been published in The Cincinnati Review, TriQuarterly, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Asian American Literary Review, and elsewhere. He received his MFA from Columbia University.

-

Public ObscenitiesA Play

CHOTON

I’m just saying like taxonomically, does it even make sense to categorize my genitalia and your genitalia as the same thing, like…

He indicates RAHEEM’s penis.

…if that’s a penis then…

He pulls his boxers down to show his own penis.

I mean what is this? It’s a polyp.RAHEEM

Okay.

CHOTON

It’s a little nunu.

RAHEEM

Well I like your little nunu…

RAHEEM examines CHOTON’s penis. He pulls back his foreskin just a bit. CHOTON winces.

CHOTON

Ow. Careful.

RAHEEM

What?

CHOTON

No it’s— it’s just sensitive.

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Public ObscenitiesA Play

CHOTON

You know that’s the only picture I’ve ever seen of him?

Chhobi hoye giyechhe…

RAHEEM

What’s that?

CHOTON

That’s what we say when somebody dies. Chhobi is picture.

RAHEEM

Shobi?

CHOTON

It’s the aspirated “chh” sound. Like “ch” then “huh”—

RAHEEM

Ch-hobi.

CHOTON

Yeah, chhobi hoye giyechhe. Has become a picture.

I mean that’s literally what he is now, right? Just like…that one picture…that after he died, somebody picked to get enlarged and framed and now…that’s the picture.

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Public ObscenitiesA Play

PISHE

You know I had one dream this like actually, some years back. Vivid dream. I am in a cinema hall…and on the screen, I am seeing one young executive…holding a portfolio…leather portfolio…entering a hotel room. And from that hotel room, through the window, can be seen a swimming pool. Ok? And in the swimming pool, he saw a beautiful looking girl. And this executive, he very much has a want to meet this girl. Then the shot changes. That girl is now sitting inside the room, wearing a green sari. And the girl says to him, I have a story to tell: when I was twelve thirteen years, I was walking by the river…suddenly a strong flood has come, and with my hands in the air like this saying save me, save me…then the picture faded. Then next scene is showing one elderly gentleman, wearing a dhuti. And until now actually shots were in color, ok? This one it became black and white. Elderly gentleman he is going, basket on his head…as he is going, absentmindedly like this, as if he is catching a fly and putting in the basket. Catching. Putting. And seeing this I turned to my friend and sayed— all this time there was no friend there, suddenly my friend was next to me— and I sayed to him: this is trash! This cinema has no meaning. And just as I sayed this, my sleep broke. And finding Pishimoni next to me, I sayed to her…what a strange and beautiful cinema I have seen. Just like this I sayed. “What a strange and beautiful cinema.”

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023- Print Books

- Bookshop

“The playwright-director Shayok Misha Chowdhury’s bilingual text and production are both gorgeously precise. . . . Even the non-Bangla-speaking members of the audience stayed rapt. . . . It was a testament to how convincingly Chowdhury had built his world—and to how carefully he had taught us to listen.” —Helen Shaw, The New Yorker [on Public Obscenities]

“[Chowdhury] directs with a restraint and subtlety that match his text. Scenes play out in a naturalistic way, mimicking the rhythms of life, and the meaning and significance accumulates over time. . . . He has admirably absorbed the ancient writerly wisdom to show, not tell." —Thom Geier, The Wrap [on Public Obscenities]

“One can walk away from Public Obscenities having experienced it not as a story but as the everyday texture of the characters’ lives, and the thick tapestry of themes that Chowdhury weaves around them - about the difficulty of communicating and of love, about the struggles to overcome strictures of caste and gender and sexuality, about memory and loss, longing and belonging.” —Jonathan Mandell, New York Theater

Shayok Misha Chowdhury writes with ruthless splendor and inventiveness about the borders of language, sexuality, the public self and the hidden life. He is a conjuror who manages to create highly theatrical work out of quotidian reality with a lightness of touch rarely seen on our stages. His debut play, written in Bangla and English, glows with allusion and homage but has its finger on the pulse of its moment.