Whiting Award Winners

Since 1985, the Foundation has supported creative writing through the Whiting Awards, which are given annually to ten emerging writers in fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and drama.

WINN – How’s Melba?

EM – She told me she could see the afterlife.

WINN – What’s it like?

EM – Or my afterlife. She said that I would be a few other things when I die, that my cells have tiny souls so when I am a piece of cheese and a pigeon, I will still be me, but my consciousness will be broken down into smaller bits.

WINN – Does that feel happy to you?

EM – I don’t care. I’ll be like a deconstructed sandwich. / Or baby.

Even as they entered, he could feel the place envelop him like a vapor with a smell of heavy, overcooked food, privation and dust. The lady taking tickets, old and wigged, with big bosoms, conspicuously switched from Yiddish to German, putting the interlopers on notice that they had been spotted. Eyeing the overblown placard for the play, showing a giant Jew with maniacal eyes throttling some stricken Gentile, he again wondered, Why did they huddle so, these people? And all the while he kept hearing this coarse, splattery jargon, so animated, with that catarrh as though a fishbone were stuck in the throat. There was a man selling hot tea from a samovar and another vending sticky cakes and ices. And the eating—everybody eating, gnawing apples and chewing sweet crackling dumplings from greasy sheets of brown paper. And that marshy barn-warmth of people huddling. It was too close for him.

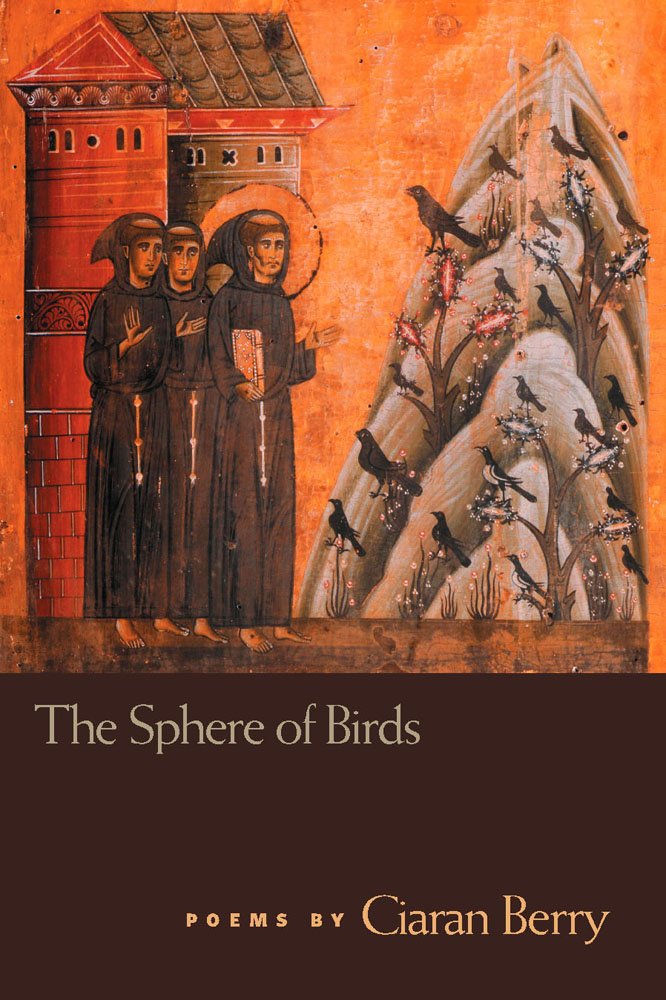

Things weather fast here, soon bird will be bone,

brittle and white, dead twig snapped underfoot

where the sky alters in seconds, shine to shower,

and harsher truths hit home hour after hour –

the sundew snagging flies, settling to eat,

a fat gull’s fractured keen that cuts through stone.

That night my daddy came in my room and sat the edge of my bed with his back to me, his long-john shirt whitening a space in the dark. He told me that had been no man at all, but a ghost, a Confederate soldier, and I stiffened in my iron bed. Here was thick with ghosts, he told me, and told me not to be afraid, but I was, that the first one I ever saw and me maybe four years old. After he left I cried with the blanket up over my head, listening for those ghost boots slapping up the stairs.

I feel I could eat women.

Driving alone, I’m hungry,

hawking bus stops and sidewalks.

Eyeballs grinding, I harden.

My mind, a bulging ice box.

My computer, a deep freeze.

The bingeing grows out of hand –

my wastebasket coughing up

the napkins hiding the bones.

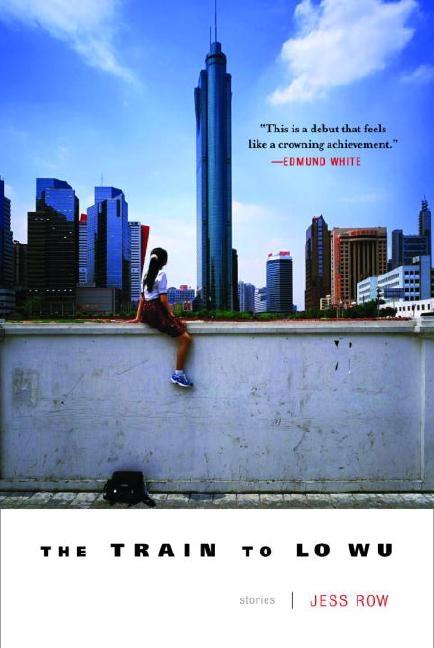

Rising at four, the students bow to the Buddha one hundred and eight times, and sit meditation for an hour before breakfast, heads rolling into sleep and jerking awake. At the end of the working period the sun rises, a clear, distant light over Su Dok Mountain; they put aside brooms and wheelbarrows and return to the meditation hall. When it sets, at four in the afternoon, it seems only a few hours have passed. An apprentice monk climbs the drum tower and beats a steady rhythm as he falls into shadow.

WINN – How’s Melba?

EM – She told me she could see the afterlife.

WINN – What’s it like?

EM – Or my afterlife. She said that I would be a few other things when I die, that my cells have tiny souls so when I am a piece of cheese and a pigeon, I will still be me, but my consciousness will be broken down into smaller bits.

WINN – Does that feel happy to you?

EM – I don’t care. I’ll be like a deconstructed sandwich. / Or baby.

Even as they entered, he could feel the place envelop him like a vapor with a smell of heavy, overcooked food, privation and dust. The lady taking tickets, old and wigged, with big bosoms, conspicuously switched from Yiddish to German, putting the interlopers on notice that they had been spotted. Eyeing the overblown placard for the play, showing a giant Jew with maniacal eyes throttling some stricken Gentile, he again wondered, Why did they huddle so, these people? And all the while he kept hearing this coarse, splattery jargon, so animated, with that catarrh as though a fishbone were stuck in the throat. There was a man selling hot tea from a samovar and another vending sticky cakes and ices. And the eating—everybody eating, gnawing apples and chewing sweet crackling dumplings from greasy sheets of brown paper. And that marshy barn-warmth of people huddling. It was too close for him.

Things weather fast here, soon bird will be bone,

brittle and white, dead twig snapped underfoot

where the sky alters in seconds, shine to shower,

and harsher truths hit home hour after hour –

the sundew snagging flies, settling to eat,

a fat gull’s fractured keen that cuts through stone.

That night my daddy came in my room and sat the edge of my bed with his back to me, his long-john shirt whitening a space in the dark. He told me that had been no man at all, but a ghost, a Confederate soldier, and I stiffened in my iron bed. Here was thick with ghosts, he told me, and told me not to be afraid, but I was, that the first one I ever saw and me maybe four years old. After he left I cried with the blanket up over my head, listening for those ghost boots slapping up the stairs.

I feel I could eat women.

Driving alone, I’m hungry,

hawking bus stops and sidewalks.

Eyeballs grinding, I harden.

My mind, a bulging ice box.

My computer, a deep freeze.

The bingeing grows out of hand –

my wastebasket coughing up

the napkins hiding the bones.

Rising at four, the students bow to the Buddha one hundred and eight times, and sit meditation for an hour before breakfast, heads rolling into sleep and jerking awake. At the end of the working period the sun rises, a clear, distant light over Su Dok Mountain; they put aside brooms and wheelbarrows and return to the meditation hall. When it sets, at four in the afternoon, it seems only a few hours have passed. An apprentice monk climbs the drum tower and beats a steady rhythm as he falls into shadow.