Stephania Taladrid is a contributing writer at The New Yorker, where she covers Latino communities across the United States. She has written on topics ranging from the 2020 Presidential election to the mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas. In 2021, Taladrid reported and produced “American Scar,” a short documentary on the environmental implications of the border wall, which received a special mention from the jury at the film festival DOC NYC. In 2022, Taladrid covered the overturning of Roe v. Wade for the magazine, producing a series of investigative stories on the end of the abortion-rights era. Taladrid is a recipient of the American Society of Magazine Editors Next Award, which recognizes outstanding achievement by journalists under the age of thirty.

-

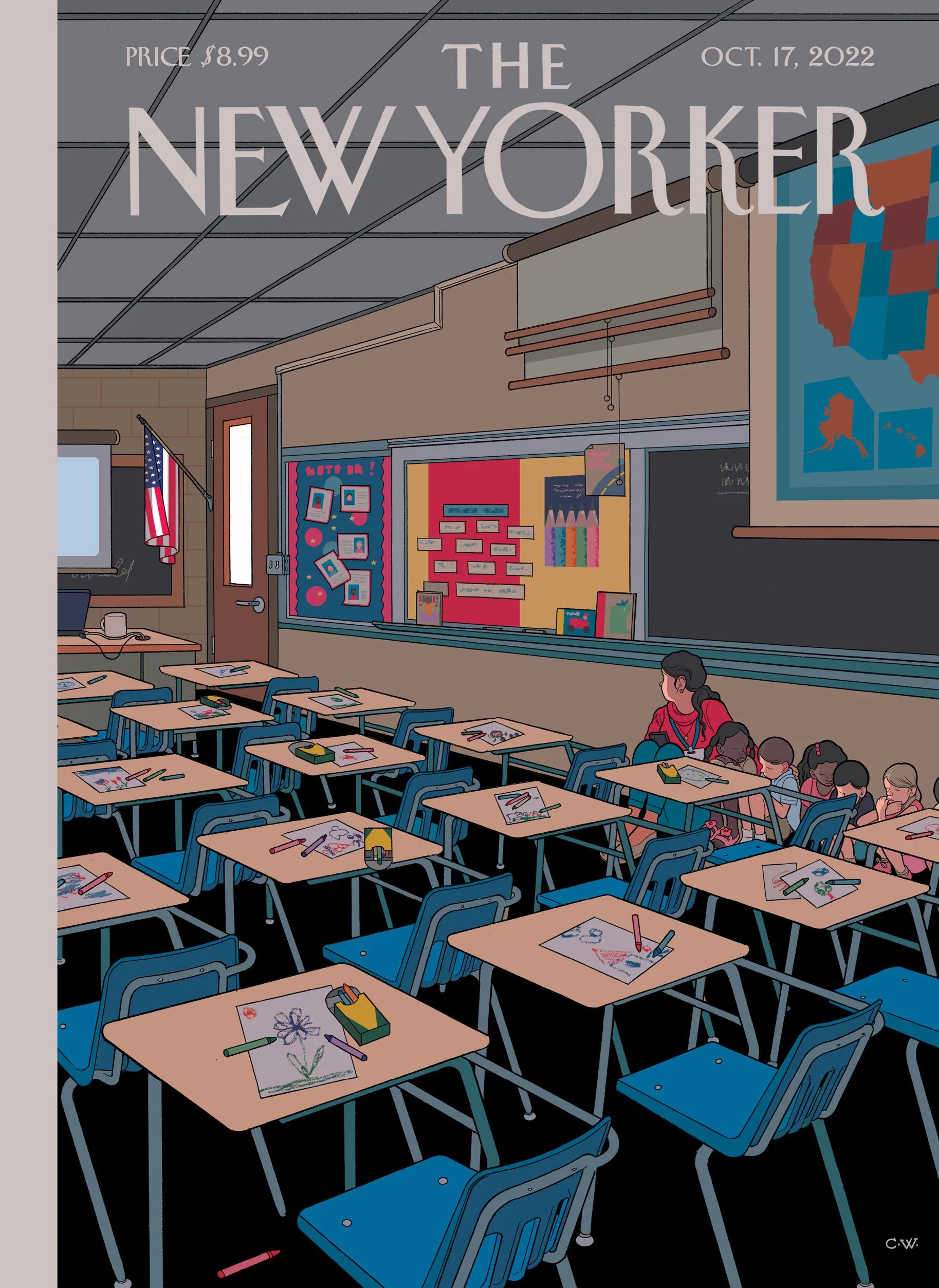

The New Yorker (October 17, 2022)From"The Post-Roe Abortion Underground"

By the time the pregnant woman for whom Anna was waiting walked up, the trailhead was quiet enough to make the chirping of birds seem jarring. As Anna pulled a plastic bag of pills from her pocket and settled across from the pregnant woman at a picnic table, she registered the fear on the woman’s face. Her distress, as Anna understood it, was less about a breach of Texas law than about the possibility that her husband, who was violent, might find out what she was doing. Hands shaking, the woman told Anna that she was already raising three children and had been trying to save enough money to remove them from a dangerous home. The prospect of having another child, she said, was like “getting a death sentence.” She couldn’t vanish from her household for a day without explanation, travel to a state where abortion is legal, and pay seven hundred dollars to a doctor for a prescription. Anna’s pills, which were free, were her best option. Taking the baggie and some instructions on how to take the medication, the woman thanked Anna and fled the park, hoping that her husband would never realize she’d been gone.

The New Yorker (Oct. 17, 2022)

The New Yorker (Oct. 17, 2022)- Print Books

-

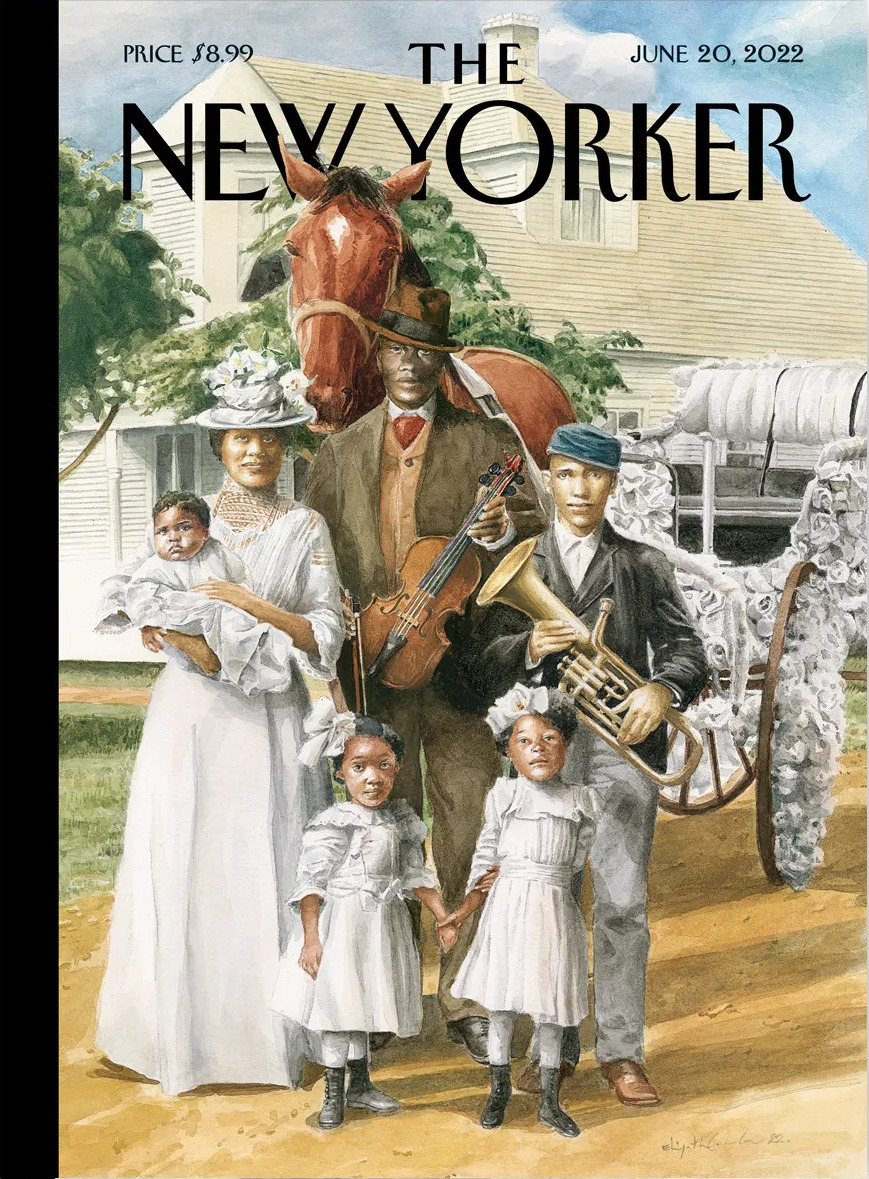

The New Yorker (June 20, 2022)From"A Texas Teen-Ager's Abortion Odyssey"

By necessity, the trip to get Laura an abortion would be a family affair. The father’s girlfriend would come along to be with Laura when she saw the doctor, and Laura’s sisters would also be joining them, the family budget being too tight to cover two days of babysitting. The father told the younger girls, in lieu of an explanation, “This is a top-secret mission.” He hoped they might never learn that Laura had been pregnant. But, in a time of regrets about his parenting judgments, taking his eldest girl out of state to have the abortion would not be one of them. He couldn’t stand the thought of subjecting her to the shame and stigma associated with the procedure in his home state. Instead, one gusty Friday afternoon in April, he, his girlfriend, and the three girls climbed into a blue Chevrolet van and headed west. The middle sister, who was eight, brought along persistent questions—Is Laura sick? And, if she is sick, why does she have to go so far away to see a doctor? The four-year-old brought along her stuffed unicorn, Chelsea. For the journey, she had put on bright-pink sneakers, and they lit up every time she tapped her feet.

The New Yorker (Oct. 13th, 2022)

The New Yorker (Oct. 13th, 2022)- Print Books

-

The New Yorker (October 17, 2022)From"The Post-Roe Abortion Underground"

The handoff was planned for late afternoon on a weekday, at an underused trailhead in a Texas park. The young woman carrying the pills, whom I’ll call Anna, arrived in advance of the designated time, as was her habit, to throw off anyone who might try to use her license plates to trace her identity. She felt slightly absurd in her disguise—sun hat, oversized sunglasses, plain black mask. But the pills in her pocket were used to induce abortions, and in Texas, her home state, their distribution now required such subterfuge, along with burner phones and the encrypted messaging app Signal. Since late June, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Texas and thirteen other states had effectively banned abortion, and more were sure to follow. In some of the states, laws that originated as far back as the nineteenth century had been restored. Providing the tools for an abortion in Texas had become a felony that could lead to years in prison, and a fellow-citizen could sue Anna and collect upward of ten thousand dollars for every abortion she was found to abet.

The New Yorker (Oct. 17, 2022)

The New Yorker (Oct. 17, 2022)- Print Books

One of the more delicate feats of great journalism is knowing how to be intensely present yet invisible. Stephania Taladrid has an extraordinary talent for releasing the storyteller in those she interviews; writing from the still eye of spiraling controversy or upheaval, she finds and protects the unforgettably human. Whether at an abortion clinic on the day Roe v. Wade is overturned or standing witness to the pain of Uvalde’s stricken parents, Taladrid draws out what otherwise would remain hidden.