From Better to Have Gone:

Small-town Minnesota is safe; boundaries are well-defined, behavior is prescribed (and mostly proscribed), and people don’t stray very far. And yet one day, in a wood-paneled dining room at the University of Denver, my mother hands an anti-Vietnam war flyer to a dark-skinned young man with long curly hair and a mustache, and a few year years later she will be living with that man in a thatch hut without running water or electricity, part of a dramatic project to build a new world. Was she searching for that adventure? She says she never dreamed she would end up there; but sometimes, we don’t know our own dreams, and we set our direction in life without realizing it.

It was the era, of course. My father was among the first generation to escape India, to an education and a promise of material comfort in America. He could have stayed, found a good job, maybe a life as a doctor, or lawyer, or engineer. Success, on the world’s terms. But the world’s terms weren’t particularly interesting to him--or to any of them. My father always said, I remember him telling me when I was a boy, “You might think we were crazy, but we really believed we could change the world, we thought anything was possible.”

It was a buoyant, ebullient, churning, history-rupturing era. Are some periods more epochal than others? People always have dreams; we are always imagining alternative worlds, alternative lives. But maybe it’s easier to follow our dreams at certain times than others. Some moments offer more scaffolding for our fantasies.

A man who lives in Auroville once told me, “Auroville couldn’t have happened without the sixties. It was just such a creature of its time. We brought everything with us—all the good stuff, all the baggage. Hope, faith, love, free love, drugs, all the sloppiness, all the energy and good vibes.”

We were sitting in his house having coffee. He was telling me how he’d dropped out of college when he got a high draft number, how he’d lived for a time in Haight-Ashbury, where everything—food, rent, clothes, marijuana—was free. Now it was the twenty-first century, decades later, and we were in Auroville: the dream, materialized. “Most of all, we were young,” he said. “We were so young and innocent, so stupid in so many ways. We were naïve; I don’t think anything could have happened without that naiveté.”

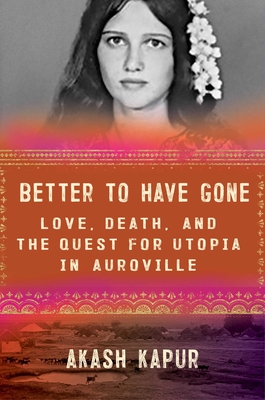

The grant jury: This book is a moving fusion of memoir, history, and ethnography that will inject new life into these forms. As an investigation into an unsolved mystery, it is compelling; as a meditation on the promise and the limitations of utopianism, it could have global resonance. The writing is unornamented, plangent, and affecting. By evoking the everyday in precise detail, Kapur brings utopianism as lived practice to technicolor life. In attempting to locate the shifting border between extremism and idealism, he has written a book rooted in memory but in dialogue with the present day.

An exploration of two troubling deaths in the author’s family, and of the forces of faith, ideology, idealism, and extremism at work in the utopian community where he grew up and returned to live as an adult.

Akash Kapur is the author of India Becoming: A Portrait of Life in Modern India (Riverhead); the editor of an anthology, Auroville: Dream and Reality (Penguin India); and the former Letter from India columnist for the International New York Times. His writing has been published in The Atlantic, The Economist, Granta, The New York Times Book Review, The New Yorker, and various other publications. He is also a Senior Fellow at the GovLab at NYU. He grew up in the intentional community of Auroville, India.

Selected Works