Fear and Fury: Bernhard Goetz and the Rebirth of White Vigilantism in America

The project:

Drawing from never-before-seen materials and challenging deeply held assumptions about what actually happened on a New York City subway car in 1984, when a white loner gunned down four unarmed Black teenagers, Fear and Fury shines new light on one of the most notorious events of the Reagan era. As this forthcoming history makes clear, that one brutal act of vigilantism, and the entire decade of the 1980s, matter in ways that we have failed to appreciate. Indeed, the toxic cocktail of white rage and resentment that bubbles below the surface of virtually every public encounter today was mixed and aggressively marketed in that moment. With stunning rapidity, an unapologetic villain would become a celebrity, his four victims would become “thugs” and “animals,” and the nation’s future would never be the same.

From Fear and Fury:

At 10:10 p.m. Shirley Cabey heard knocking at her apartment door. This was unsettling for so many reasons. But as she peered out of the peephole, she relaxed. It was just her neighbor. She was smiling as she unlocked the door, but felt her heart start to beat a little too fast after the woman standing in front of her asked, anxiety straining her voice, if Shirley’s son Darrell was at home. Why, Shirley asked with mounting dread. Because, her neighbor explained, she had just received a call from the transit police informing her that her own son had been shot in the city. But that couldn’t be right, she went on. Her boy was accounted for. Maybe the officers had meant to call Shirley, she ventured nervously? After all, these women had similar last names, and Shirley’s number was unlisted.

As if she were wading through molasses, Shirley turned, made her way over to the phone that hung on the living room wall, and began to dial.

Thirty minutes later she was sitting in her cousin’s car, with her mother in the backseat, racing to the emergency room at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village. As the trio sped past countless high rises framed by the night sky, many with small Christmas trees twinkling hopefully in their windows, Shirley’s mother tried valiantly to persuade her daughter that even if it was their Darrell, things might not be that bad. Shirley clung to these words. Her mom had spent her career working as a nurses’ aide. She would know.

But when Shirley finally managed to get past the desk clerk, and to meet with the doctor who had sat her down in the cold and harshly lit family room near the ER, she learned that her son’s situation was actually worse than bad. “Mrs. Cabey,” he told her solemnly, “there was nothing we could do. The bullet severed his spinal cord. Darrell will be paralyzed from the waist down. He will never walk again.” All Shirley could manage to ask was if Darrell knew. No, the doctor mumbled. It would be better for her to explain this to him in the morning. For now, someone else told her, it would probably be best if she headed home. Dazed, Shirley complied.

The next morning, she rushed back to the hospital. Retracing the steps that her son had taken just the day before, Shirley boarded the M55 bus and then switched to the downtown 2 train. Eventually she arrived at 14th Street; the very same subway station that the man who had shot her son had entered less than 24 hours earlier.

As Shirley stood looking down at her barely recognizable boy, hooked up as he now was to the many hissing tubes and whirring machines that tethered his slight frame to the dimly lit ICU bed, she felt helpless. According to the nurses, Shirley would only be allowed a ten-minute visit. Part of her was relieved. Perhaps Darrell would just keep sleeping and then she might not have to tell him, not just yet, how badly he had been hurt.

As if he sensed his mother’s presence, Darrell stirred, and with his fingers fluttering weakly, he tried to reach out to her. But then his face began slowly to contort in confusion and fear as he registered the anguished look in his mother’s eyes. Unsure what was going on and overwhelmed by his mother’s pain, Darrell began to choke up, tears coming unbidden and uncontrollably as he looked up at her and whispered, “I’m sorry, Mama; I am so sorry.”

The grant jury: A masterful, fine-tuned work by a world-class historian. Working from new and archival interviews, newspaper accounts, legal files, and more, Heather Ann Thompson handles this once-notorious, now almost-forgotten event with meticulous care. She moves deftly among points of view to create a kinetic, minute-by-minute account and gives us what the media of the day missed: an understanding of how victims had their victimhood taken from them. Fear and Fury will be a landmark reframing of the modern resurgence of white vigilante violence.

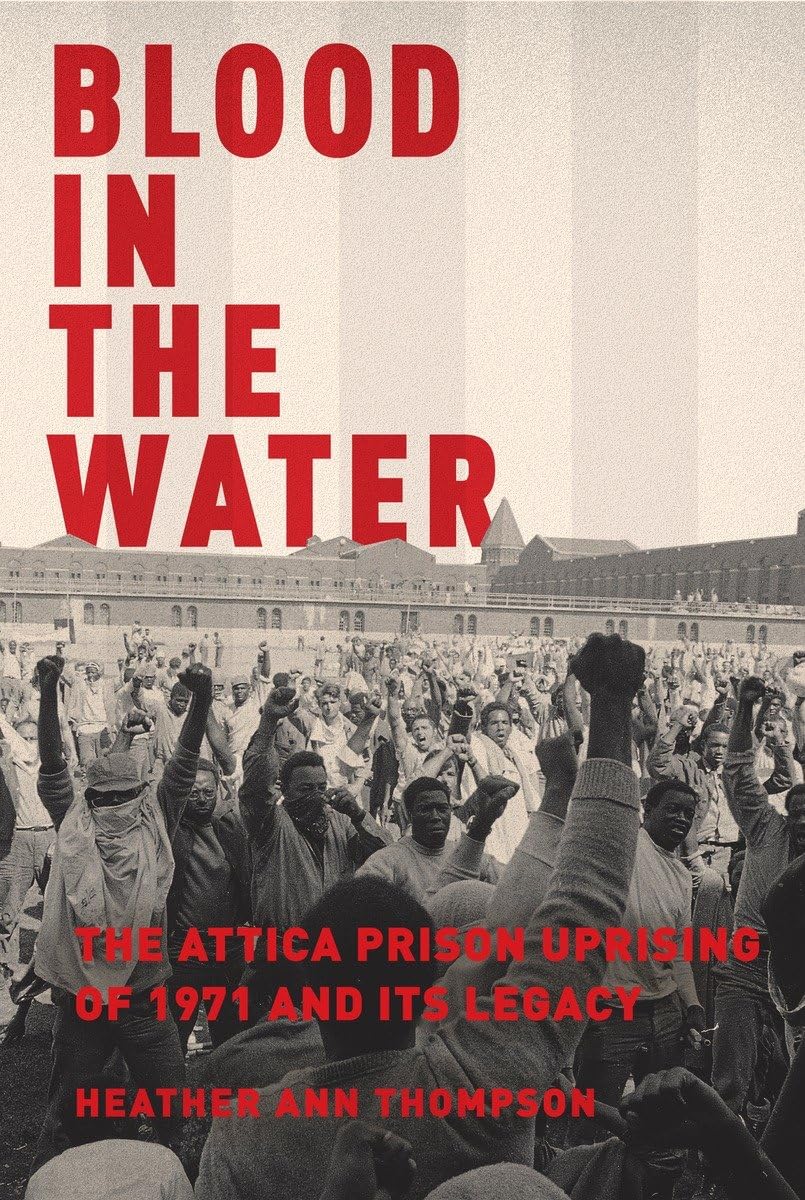

Heather Ann Thompson is a historian and the Pulitzer Prize- and Bancroft Prize-winning author of Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. This 2016 book received five additional book prizes and was also a finalist for the National Book Award and the LA Times Book Prize. Thompson is also the author of Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City. She writes regularly on the criminal justice system for myriad publications, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, TIME, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker. Thompson’s policy work includes serving on a National Academy of Sciences blue-ribbon panel that studied the causes and consequences of mass incarceration in the US. She also co-runs the Carceral State Research Project at the University of Michigan.

Selected Works