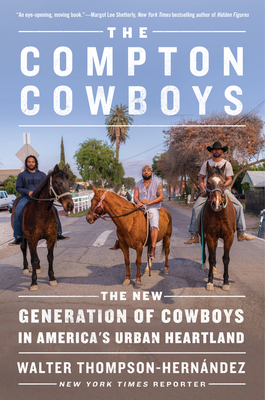

The Compton Cowboys: A New Generation of Cowboys in America's Urban Heartland

The project:

The Compton Cowboys is a story about trauma and transformation, race and identity, compassion and belonging in one of the most stigmatized cities in America. Drawing on a year-long immersion with a group of friends who choose horses over gangs and violence, and who struggle to keep their ranch from going under, Walter Thompson-Hernández pushes back against stereotypes to reveal an urban community in complexity, tragedy, and rebirth.

From The Compton Cowboys: A New Generation of Cowboys in America's Urban Heartland:

Long before Anthony learned to put a saddle on a horse, before he learned how to keep a Stetson crisp by brushing it counter-clockwise, he was a gangster. He’d been jumped into the Acacia Blocc Crips at the age of eight.

It was shortly after Anthony dropped out of middle school when Black told him about a woman he wanted him to meet. When they arrived, they were hit by the pungent smell of hay and stables, and the whimsical and frequent neighs of the horses. A large sign above the entry read, “Compton Junior Posse: Equestrian Club, Est. 1988” and showed a horse rearing, as if it meant to throw off its rider. Anthony had never seen that word before, “equestrian,” but a posse was like a gang, wasn’t it? If so, then what did that make a cowboy? He didn’t have much time to figure it out, because a woman was already walking toward them. She was wearing a cowboy hat with a blue stripe and clutched beneath her arm was a dusty leather saddle. She had kind, sparkling eyes, and a purposeful stride. “You must be Anthony,” Mayisha said, extending her free hand.

As Anthony’s first year in the Los Angeles County Jails began to round out, he found himself spending less and less time on the prison yard and more time in the solitude of his own cell. Though it had been years since he last rode a horse, in isolation his mind kept returning to the horses at Mayisha’s ranch. Minutes turned into hours and hours turned into days as he dreamed about the feeling of riding bareback through the streets of Compton. When his cell gates opened up twice a day for recreation, he stayed inside and did pushups. He was slowly withdrawing from prison life and an environment meant to control him.

He began to draw aspects of the ranch that were vivid in his memory. He drew the contour of the giant oak tree that housed hundreds of chirping birds every morning. He drew groups of black boys and girls riding on horses, wearing light blue t-shirts like the ones Mayisha required everyone to wear on the ranch.

The first time he drew horses, they looked nothing like horses. The figures were weirdly shaped, brown blotches that barely resembled an animal. He began checking out books out from the prison library. He checked out children’s books, history books, and animal books; anything with images that could serve as a model to improve his drawing. Inmates weren’t allowed to have color pencils or paint because correctional officers feared they could be used to make makeshift narcotics that could be sniffed or ingested, but Anthony devised a method for creating watercolor in his cell using Skittles candy, a highly sought-after favorite among inmates. If the candy’s dye could leave a mark on his fingers, he thought, then they would be sure to leave a mark on a sheet of paper. He dipped some into a bowl of water one afternoon and shouted with excitement, almost loud enough for the guards to burst in and shut his secret operation down.

Anthony learned that if he wanted to paint a brown horse, he should mix red, blue, and yellow candies. In the early hours of the morning, while his cellmate groaned in the top bunk, Anthony crouched near the bars, painting under the dull, flickering light outside of his cell. Every week on the phone, he told Lozita, his girlfriend and mother of his two children, about his plans to work on the ranch once he got out. He told her that if he hadn’t stopped riding horses, he would never have gone to jail.

The grant jury: A captivating, sustained examination of a charismatic group of underprivileged men and women who challenge the stereotypes of “gangsta” and cowboy. Everything about this set of interlocking stories of transformation and struggle is compelling: the camaraderie as an alternative to urban gang life (‘Streets raised us, horses saved us’); what the cowboy subculture suggests about the possibilities of intimacy and community in the face of violence; and the universal themes of redemption and finding a sense of self. The book has the potential to disrupt some of the prevalent toxic stereotypes about black urban experience. Thompson-Hernández writes with rigor, gusto, and compassion, allowing his protagonists—who have given him unparalleled access—to be more than victims or villains. There is a genuine hope in these pages that is neither blind nor cheap: it's vexed and it's real and it's genuine, bringing a sense of possibility rather than despair to our conversations about inequality in American life.

Walter Thompson-Hernández is a Los Angeles–based New York Times reporter and host. Before joining the Styles desk, he was part of a multimedia Times reporting team called “Surfacing” that covers marginalized and offbeat communities. He has written for NPR, Fusion, the Guardian, Remezcla, and other media outlets, and has reported from every continent and throughout the United States. He received his master’s degree in Latin American Studies from Stanford University, and was enrolled in the UCLA Chicano Studies Ph.D. program for one year before leaving to write for the Times. Before graduate school, Walter played professional basketball throughout Latin America.

Selected Works