My father had decided to teach me how to grow old. I said O.K. My children didn't think it was such a great idea. If I knew how, they thought, I might do so too easily. Oh, I said, it's for later, years from now. And besides, if I get it right, it might be helpful to you kids.

They said, Really?

He wanted to begin as soon as possible. For God's sake, he said, talk to the kids later. Listen to me. You're so distractible.

We should probably begin in the beginning. Change. First, there is change, which nobody likes. Even men. You'd be surprised. You can do little things – you can put cream in the corners of your mouth and the heels of your feet. But here's the main thing. I wish your mother was alive – not that she had time.

But Pa, I said, Mama never knew anything about cream. I didn't say she was famous everywhere for not taking care.

Forget it, he said. But I must mention squinting. Don't squint. Wear your glasses. Look at your aunt, so beautiful once. I know someone has said men don't make passes at girls who wear glasses, but that's an idea for a fool. There are many handsome women who are not exactly 20/20.

Please sit down. Be patient. The main thing – when you get up in the morning, you must take your heart in your hands. Just do this every morning.

It's a metaphor, right Pa?

No. You can do this.

In the morning, do a few little exercises for the joints. It's not too much. Put your hands, like a cup, over-under the heart. Under the breasts. It's probably easier for a man. Then, talk softly. Don't yell. Under your ribs, push. When you wake up, you must do this. Heck, stroke a little. Don't be ashamed. Very likely, no one will be watching. Then, you must talk to your heart. Say anything, but be respectful. Say – maybe say, Heart, little heart, beat soft, but never forget your job. The blood. You can also whisper also, Remember.

For instance, I said to it yesterday, Heart, Heart, do you remember my brother, how he made work for you the day when he came to the store where I was working and he said, Your boss's money, right now? How he put a gun in my face, and I said, Grisha, are you crazy? Why don't you ask me at home? I would give you money. He was only a kid. He said, Who needs your worker's money? For the movement – only from your boss I want. Little Heart, you work like a bastard, like a dog. Bang! Remember? That's the story I told my heart yesterday, my father said. And what a racket it made to answer me. I remember, till I was dizzy with the thumping.

But why did you do that, Pa? I don't get it.

But don't you see? It's good for the old heart – to get excited – just as good as for the person. Some people go running too late in life – for the muscles, but the heart knows the real purpose: expansion of the arteries, a river of blood cleans off the banks. I myself would rather remind the heart how frightened I was by my brother than go running in a strange neighborhood miles and miles with the city so dangerous these days.

I said, Oh. Then I said, Okay.

I don't think you listened, he said. As usual, you're worried about the kids. If you were better organized, you wouldn't have worries.

I stopped by a couple of weeks later. This time, he was annoyed.

Why did you leave the kids home? If you keep doing this, they'll forget who I am.

They won't forget you, Pa. Never in a million years.

You think so, huh? God has not been so good about a million years. He put it down in writing 5,600-5,700 years ago for us Jews in the book. You know, our book, I suppose.

Well, probably a million years is too close to His lifetime, if you could call it life, what He goes through. I believe He said several times, when He was still in contact with us, I am a jealous god. I am a jealous god, and here and there, he makes an exception. I read there are 3,000-year-old trees somewhere in some God-forsaken place. Of course, that's how come they're still alive. We should all be so God-forsaken.

But no more joking. I've been thinking what to tell you. First of all, maybe 20-30 years from now, you'll begin to get up in the morning, 4 or 5 a.m. You'll remember everything you did, didn't, what you omitted, who you insulted, betrayed. That is the worst. Do you remember, you didn't go to see your aunt, she was dying? That will be on your mind like a stone. Of course, I, myself, did not behave so well. Still, I was busy those days. Long office hours. It was usual in those days for doctors to make house calls. No elevator, fourth floor, fifth floor, even a nice Bronx tenement. But this morning, I mean, this morning, a few hours ago, my mother, your babushka, your grandma, came into my mind and looked at me.

Have I told you I was arrested in Russia? Of course I've told you. I was arrested a few times, but this time, for some reason, the policeman walked me past the office, the police station. I saw my mom up through the window. She was bringing me a bundle of clean clothes. She put it on the officer's table. She turned. She saw me. She looked at me through the glass with such a face, eye-to-eye, with despair. No hope. This morning, 4 am, I saw once more how she sat there, very straight. Her eyes. Because of that look, I did my term. I finished my sentence the best I could. I finished up six months in Arkhangelsk, then no more. No more, I said to myself, no more saving imperial Russia, the great pogrom maker, from itself.

Oh, Pa.

Don't make too much out of everything. Well, anyway, I want to tell you, also, how the body is your enemy. I must warn you, it is not your friend like when you were a youngster. For example. Greens. I believe they are overrated. Some people think that they can cure cancer. It's a style now. My experience with maybe 100 patients proves otherwise. Greens are helpful to God. That fellow Sandberg, the poet – I believe from Chicago – he explained it. Grass tiptoes over the whole world and holds it in place – except the desert, of course, everything there is loose, flying around.

How come you bring up God so much? When I was a kid, you were a strict atheist, Pa. You even spit on the steps of the synagogue.

Well, God is very good for conversation, he said. By the way, I believe I have to tell you a few words about the stock market. Your brother-in-law is always talking how brilliant he is investing. My advice to you: Stay out of it.

But people are making money. A lot. Read the paper. Even kids become millionaires.

But what of tomorrow?

So tomorrow, I said, they make another million.

No, no, no. I mean, tomorrow. I was there when tomorrow came in 1929, and so I say to them and their millions, Ha-ha-ha, tomorrow will come. Go home now. I have a great deal more to tell you. Somehow, I'm always tired.

I'll go in a minute, I said, but I have to tell you something, Pa. I had to tell him my husband and I were separating, maybe even divorce, the first in the family.

What? What, are you crazy? I don't understand you people nowadays. I married your mother when I was a boy. It's true, I had a first-class mustache, but I was a kid. And you know? I stayed married until the end. Once or twice, she wanted to part company. Not me. The reason, of course, she was inclined to be jealous.

He then gave me the example I'd heard five or six times. What it was. One time, two couples went to the movies. Arzemich and his wife, you remember. Well, I sat next to his wife, the lady of the couple, by the way a very attractive woman, and during the show, which wasn't so great, we talked about this, that, laughed a couple of times. When we got home, your mother says to me, Okay, any time you want, right now, I'll give you a divorce. We will go our separate ways. Naturally, I said, What? Are you ridiculous?

My advice to you – stick it out. It's true, your husband, he's a peculiar fellow, but think it over. Go home. Maybe you can manage, at least until old age. Then, if you still don't get along, you can go to separate old age homes.

Pa, it's no joke. It's my life.

It is a joke. A joke is necessary at this time. But I'm tired.

You'll see, in thirty, forty years from now, you'll get tired often. Doesn't mean you're sick. This is something important that I'm telling you, so listen. To live a long time, long years, you have to sleep a certain extra percentage away. It's a shame.

It was at least three weeks before I saw him again. He was drinking tea, eating a baked apple, one of twelve my sister baked for him every ten days. I took another one out of the refrigerator. "Fathers and Sons" was on the kitchen table. Most of the time he read history. He kept Gibbon and Prescott on the lamp stand next to his resting chair. But this time, thinking about Russia, for some reason in a kindly way, he was reading Turgenev.

You're probably pretty busy, he said. Where are the kids, with the father? He looked at me hopefully.

No hope, Pa.

By the way, you know this fellow, Turgenev? He wasn't a show-off. He wrote one book. He became famous right away. One day he went to Paris, and in the evening he went to the opera. He stepped into his box, and just as he was sitting down, the people began to applaud. The whole opera house was clapping. He was known. Everybody knew his book. He said, I see Russia is known in France.

You're a lucky girl, you know, that these books are in the living room, more on the table than on the shelf like in some people's houses.

That's true, Pa, I said.

Excuse me, also about Turgenev. I don't believe he was an anti-Semite. Of course, most of them were, even if they had brains. I don't think Gorky, Gogol, probably a little, Tolstoy, no, Tolstoy had an opinion about the Mexican-American war. Did you know? Of course, most of them were anti-Semites. Dostoevsky, oy. It was natural, it seems. Why is it we read them with such interest and they don't return the favor?

That's what we women writers say about men writers, Pa.

Please don't start in. I'm in the middle of telling you some things you don't know. Well, I suppose you do know a number of Gentiles, you’re more in the American world. I know very few. Still, I was telling you – Jews were not allowed to travel in Russia. I told you. But a girl, if she was a prostitute, could go anywhere. Also a Jew if he was a Merchant First-Class. Even people with big stores were only second-class. Who else? A soldier. He served a certain amount of time, nobody could arrest him. Even if he was a Jew. If he killed someone, a policeman could not arrest him. He wore a certain hat. Why am I telling you all this, anyway?

Well, it is interesting.

Yes, but I'm supposed to tell you a few things, give advice, a few last words. Of course, the fact is I'm obliged, because you are always getting yourself mixed up in politics. You also have an idea because I was a kid running in and out of prison, also your mother, it's okay for you. It is not okay in this country, which is a democracy. And you are running in the street like a fool. Your cousin saw you a few years ago, suspended, sitting with other children in the auditorium, not allowed to go to class. You thought Mom and I didn't know.

Pa, that was 35 years ago in high school. Anyway, what about Momma? You mentioned the Arzemich family. She was a dentist, wasn't she?

Right. Capable woman. Very capable woman.

Well, Mama probably felt bad about not getting me to school, and, you know, becoming something. Like, having a profession like Mrs. What's-Her-Name. I mean, she did run the whole house and the family and your office, and people came to live with us. But she was sad about that, surely. That she didn't have a chance.

He was quiet. Then he said, You're right. It was a shame. Everything went into me. I should go to school. I should graduate. I should be the doctor. I should have a profession. Poor woman. She was extremely smart. At least as smart as me. In Russia, in the movement, you know, when we were youngsters, she was considered the more valuable person. Very steady, honest. Made first-class contact with workers, a real organizer. I could only be an intellectual. But maybe if life didn't pass so quick, speedy, a winter day – short. So short. You know, also, your mother was very musical, and she had perfect pitch. A few years ago, your sister made similar remarks to me about Momma. Questioning me, like history is my fault. Your brother only looks at me the way he does – not with complete approval.

Then, one day, my father surprised me. He said he did want to talk a little, but not too much about love or sex or whatever it's called – its troubling persistence. He said that might happen to me, too, eventually. It should not be such a surprise. Then, a little accusingly, After all, I had been a man alone for many years. Did you ever think about that? Maybe I suffered. Did it even enter your mind? You're a grownup woman, after all.

But Pa, I would never have thought about bringing up anything like that. You and Ma were so damned puritanical. I never heard you say the word “sex” until this day. Either of you.

We were serious Socialists, he said. So? He looked at me, raising one nice, thick eyebrow. You don't understand politics too well, do you?

Actually, I had thought of it now and then, his sexual aloneness. I was a grownup woman. But I turned it into a tactful question: Aren't you sometimes lonely, Pa

I have a nice apartment.

He closed his eyes. He rested his talking self. I decided to water the plants. He opened one eye. Take it easy. Don't overwater.

Anyway, he said, only your mother, a person like her, could put up with me. Her patience – you know, I was always losing my temper. But finally, with us, everything was all right, all right, accomplished. Do you understand what that means? Your brother and sister finished college, married and we had a beautiful grandchild. I was working very hard, like a dog. We were only fifty years old then, but look, we bought the place in the country, and your sister and brother came often. You yourself running around with a dozen kids in bathing suits all day. Your mama planting all kinds of flowers every minute. Trees were growing. Your grandmother, your babushka, sat on a good chair on the lawn. In the back of her were our birch trees. I'd put in a nice row of spruce. And one day, in the morning, she comes to me, my wife. She shows me a spot over her left breast. I know right away. I don't touch it. I see it. In my mind I turn it this way and that. But I know in that minute, in one minute, everything is finished, finished – happiness, pleasure, finished, years ahead, black.

No. That minute had been told to me a couple of years ago, maybe twice in ten years. Each time, it nearly stopped my heart, you know.

He recovered from the telling. Now listen, this means, of course, you should take care of yourself. And I don't mean eat vegetables. I mean go to the doctor on time. Nowadays a woman as sick as your momma would live many years. Your sister, for example, after terrible operations – heart bypass, colon cancer – more she hides from me. She is running around to theater concerts, she probably supports Lincoln Center. Ballet, chamber symphonies – three, four times a week. But you must pay attention. One good thing, don't laugh, is bananas. Really. Potassium. I myself eat one every day.

But seriously, I'm running out of advice. It's too late to beg you to finish school, to get a couple of degrees, a decent profession, be a little more strict with the children. They should be prepared for the future. Maybe they won't be as lucky as you. Well, no more advice. I restrain myself.

Now I'm changing the whole subject. I will ask you a favor. You have many friends – teachers, writers, intelligent people. Jews, non-Jews. These days, I think often, especially after telling you the story a couple of months ago, about my brother Grisha. I want to know what happened to him.

Well, I guess you know he was deported around 1922, right?

Yes, but why did they go after him? The last ten years before that, he'd calmed down quite a bit, had a nice job, I think. But that's what they did – did you know that? Even after the Palmer raids, they went here and there. They picked up young people at home, the Russian Artist's Club, other places. Of course, you weren't even around yet, maybe just born. They thought a big American revolution would come from these kids to imitate Russia. Some joke. Ignorance. They already didn't like Lenin. More they liked Akunin. Emma Goldman, her boyfriend, I forgot his name.

Berkman.

Right. They were shipped, I believe, to Vladivostok. There must be a file somewhere. Archives salted away. Why did they go after him? Maybe they were mostly Jews. Anti-Semitism in the American blood from Europe – a little thinner. But why didn't we talk, he and I? All the years not talking. Me seeing sick people day and night. Strangers. And not talking to my brother till all of a sudden he's on a ship. Gone.

Go home now. I don't have much more to tell you. Anyway, it's late. I have to prepare now all my courage, not for sleep, for waking in the early morning, maybe 3 or 4 AM. I have to be ready for them, my morning visitors – your babushka, your momma, most of all, to tell the truth, your aunt, my sister, the youngest. She said to me that day, in the hospital, Don't leave me here. Take me home to die. And I didn't. And her face looked at me that day, and many mornings looks at me still.

I stood near the door, holding my coat. A space, at last, for me to say something. My mouth opened.

Enough already, he said. I had the job to tell you how to take care of yourself, what to expect, what is coming. About the heart – you know, it was not a metaphor. But in the end the great thing, a really interesting thing, would be to find out what happened to our Grisha. You're smart. You can do it. Also, you'll see. You'll be lucky in this life to have something you must do to take your mind off all the things you didn't do.

Then he said, I suppose that is something like a joke. But my dear girl, very serious.

Thank you.

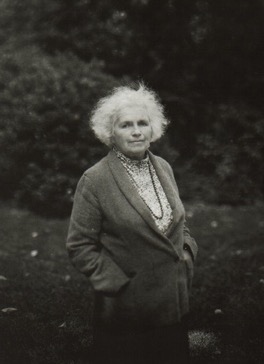

Born in the Bronx in 1922, Grace Paley was a renowned writer and activist. Her Collected Stories was a finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. She was the author of five collections of stories and five collections of poems; Fidelity, her final volume of poetry, was published after her death in Vermont on August 22, 2007.

Photo Copyright Gentl & Hyers/Arts Counsel, Inc.