It is an honor to be here, for me. I’ve watched the Whiting program for ten years, and there isn’t a doubt in my mind that it’s the best in the country. I want the trustees to know that this is known, it’s a model program.

If you look at the list of people, over the ten years, who have received the award, it’s absolutely astonishing.

It’s true, I supposed, that it represents a small amount of money in corporate terms, but in terms of leverage, it’s just been remarkable. Because, what happens with this money is, it’s time, it’s money with which to buy time. It’s very difficult in American society to get time to do work. People have to make a living. And so, I don’t even think of these prizes as being money. I think of them as being time. And I think that the record of the program speaks for itself.

This is a short speech. As I outline what I suppose to be some bad news, I hope you will bear with me and not jump to conclusions about my reasons for doing so. Much of what I’m about to say is familiar. Banal, perhaps. Reverend Wildmon, as well as various crypto-fascist, crypto-Christian anti-humanist and reactionary groups in search of purity and the almighty dollar. We turn away from their shrillness, their reductiveness, as well we should. But their existence should surely not preclude an open discussion of some of the conditions that, in part, gave rise to them in the first place. There seem to be quite a few grey beards who believe our culture to be in grave danger. Saul Bellow thinks the very fabric may be able to give way. Norman Mailer is surprised that the new generation has any interest in writing novels. Harold Bloom makes the valid point that very few English literature departments in the academy have any interest in literature at all, except as flax from which to weave elaborate tapestries of theory, which Stanley Fish goes on to describe as “utterly useless outside their hermitic disciplines.” I could go on, testaments to an acceleration of the widening gyre, but you get the idea.

Well, haven’t the grey beards always said everything is going to hell in a handcart? Generation after generation? Yes, they have, certainly they have. But we must also consider the famous remark of Delmore Schwartz, who first said, “Just because I’m paranoid, that doesn’t mean there isn’t somebody following me.”

As well, we know that the last time the boy cried wolf, the wolf was indeed there, and the flock decimated. So, what’s wrong? Which signs are significant, and how do we read the signs? When is it appropriate to use that famously fragile and often abused tool called common sense, and when is it better to go to psychology, sociology, and the other soft sciences? A hodgepodge of science, we incarcerate a higher percentage of our people than any other country in the world, save Russia. And after the elections the crime bill, et cetera, we will doubtless be back in first place, or last place, depending on how you look at it. Nevertheless, drugs and drug violence continue. A doctor friend of mine working in the emergency room of a big city hospital testifies that the teenagers with gunshot wounds who make up a large part of his daily practice are deeply and genuinely surprised that it hurts to get shot. There is also non-drug violence of an apparently new variety, or at least at apparently new levels. Children upon children. The five-year-old Norwegian girl stripped, kicked, beaten and left to freeze to death by six and seven year olds. Followed by a government decision to cease broadcasting of a violent American made children’s TV show to whose vocabulary the kids made several references. The two British kids who kidnapped and killed a younger child after seeing a particular violent film aimed at young audiences.

The establishment of a causal link and these and many other cases is caught up in a soft science gridlock. As is the whole question of the effects of hyperbolic media violence on people in general. Liberal humanists seed these questions to the social scientists, or to the Reverend Wildmons of this world at their own peril, it seems to me. We are awash in violence, sufficiently so as to trivialize it. Televisions, movies, and yes, even books. Genre stuff where people skin other people alive, commit serial murders, torture children and the like; pop stuff that outsells real literature a hundred to one. All these work on us to the point where we share something with the teenagers in the emergency room: we’re surprised that it’s done something to us. That it, in another sense, hurts. I have no solutions, of course, but I do believe it’s hurting us, and I think we should face up to it.

Signs. Decadent materialism. Consumerism. The artful complex web of lies created by the advertising industry, which, needless to say, has moved light years away from its professed role as provider of necessary information. Billboards on the highway, for instance, helping the buyer to make intelligent choices. The goal now is the creation and maintenance of an alternate reality. The assertion of the existence of a world which does not, in fact, exist, and a concomitant conditioning of the people to bend every effort to become part of that world. The last thing the advertising people want, is for us to gain deeper knowledge and deeper awareness of the world in which we actually live. Our attention must be kept on the fantasy, and the accumulation of various symbols, icons, styles, and attitudes which tease us into the belief that we are moving closer to that fantasy world, which is in fact nonexistent and unattainable.

It has moved past buying and selling into our very perception of reality. Prozac is the fifth largest selling drug in the United States. If there are that many seriously depressed people, what does that say about us? If there aren’t, what does it say that so many are taking the pill? Is there an operative dynamic to this phenomena that transcends the medical question of depression? It would appear so. Signs of the progressive weakness of the educational system, especially—but not confined—to K through 12. This is not exclusively an urban problem, not simply a function of the decline of the cities. All over America, our young people are falling further behind their contemporaries in the industrialized world. The teaching profession—once held in high esteem by the citizenry—is now more often thought of as just another branch of the civil service.

We seem, as a culture, to be in a state of amnesia, towards the future as well as the past. We are hypnotized by the emergencies of the present. Too many of us have lost the sense of our country as a continuous narrative. Well, I could go on. The degrading chokehold of pop culture, the uncoupling of individual responsibility from individual action. This is familiar stuff. And I can anticipate that some of my friends in the audience tonight are already thinking, “Hey, Frank! Lighten up, this is supposed to be a celebration, after all.” Well, yes. But I must work to make the point that America has never needed its literary artists more than it does now.

Consider the irony of the information explosion: faxes, modems, internets, 500 channels, computers, Xeroxes, wireless communications, fiber optics, and so on. Great! And yet, information by itself remains only that: information. It is not—as President Clinton pointed out last month—knowledge. It remains increasingly difficult for us to get a grasp on what is actually happening to ourselves and our country. We sense the gradual fade out of a moral and ethical consensus. A fracturing, or slippage, of whatever bedrock it is upon which our assumptions about civilized life have rested. And how can we think about these problems when we are surrounded by so much noise? The white cacophony of violence, lies, speed, abject materialism, and spiritual confusion, which has become as natural to us as the sound of the wind in the trees.

How do we proceed? We can consider other crises in our past. Let me quote a few lines from “As I Sat Alone by Blue Ontario’s Shores”, Walt Whitman’s meditation of the reuniting of the American people after the Civil War: “Underneath all, individuals. I swear, nothing is good to me now that ignores individuals. The American compact is all together with individuals.” Whitman was speaking of the people, protecting and celebrating the individuality of each and every one of us. By extension, this is surely the literary artist’s work. No matter how difficult the conditions, we have at least a place to start, with ourselves. With who we are. If we work hard, the pressures of our individual souls will animate our creations. As Faulkner puts it, “We will create out of the materials of the human spirit, something which did not exist before.”

As Whitman refused to give up after the Civil War, so Faulkner refused to give up after World War II, when the crisis was our realization that we had the power to end life on the planet. In Stockholm, 44 years ago, he said—and I paraphrase—“Our tragedy today is a general and universal fear, so long sustained by now, that we can even bear it. Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself, which alone can make good writing, because only that is worth writing about. He must learn them again, until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man.

“I believe that man will not merely endure, he will prevail. He is immortal; not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul. A spirit, capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s duty is to write about these things; it is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice, which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars, to help him endure and prevail.”

It amazes me how Faulkner’s language from 44 years ago seems so entirely appropriate now. I was only 12 years old at the time of that speech, but I remember reading an attack of it. Concepts of the soul and spirituality were assumed to be the exclusive concerns of religion. Of course, they were not then, nor are they now. They are what all serious art is about. They are fundamental concerns of human culture, despite the fact that the questions raised will never be fully resolved.

So finally, in answer to my own question, how do we proceed? What we do, is work. What we do, is write. Whatever the distractions, we stick to it, come what may.

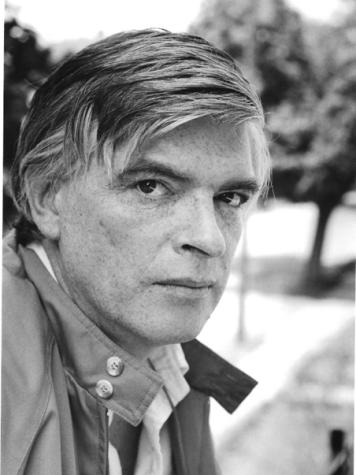

Frank Conroy (1936 - 2005) taught at George Mason University, MIT, and Brandeis University. He was Director of Literature at the National Endowment for the Arts before becoming the Director of the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa. Conroy wrote an autobiography, Stop-Time, a collections of short stories, Midair, a novel, Body & Soul, a book of essays, Dogs Bark, but the Caravan Rolls On and a memoir, Time & Tide. His work appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, GQ, Harper’s Magazine, and Partisan Review. He was an accomplished jazz pianist.