Japanese American Historical Plaza

The project:

Japanese American Historical Plaza is a book of creative nonfiction inhabiting the ongoing afterlife of the mass incarceration of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans during WWII. It is a memoiristic travelogue through the ruins of the incarceration sites; memorials and museums; representations of incarceration in popular culture (art, literature, film); present-day legislation; and the lives and stories of former incarcerees and their descendants.

From Japanese American Historical Plaza:

My great-aunt Joy was four when she and her family were removed from their home and sent to a detention center at the Santa Anita racetrack, in Arcadia, California. The only thing she remembered, and could hear, with perfectly clarity—because she delivered it directly to our table at the Sea Empress restaurant—was her mother’s constant sneezing. They lived, for three months, in a horse stall. There was hay on the floor. They stuffed their pillows with it.

Then they were on a train. They did not know where they were going, or if where they were going would be better or worse than resting their faces on bags of hay in a horse stall. I remember dust and dryness, is the first thing Joy said when I asked her what she remembered of her time in Poston—dust and dryness, which is a memory shared by many who were incarcerated in the desert, including those—because the dust must have blown very hard—who were not there. It was as if the dust was orchestrated to extend their traveling blindly. The second thing Joy said was: winter was very cold.

Poston was the largest of the ten main concentration camps, and the first to open. It was proposed to—and was met with the objections of—the Colorado River Indian Tribal Council, as an opportunity for their reservation to be developed. The Japanese Americans cultivated farmlands, made adobe bricks, built an irrigation system that drew water from the Colorado, and built 54 schools for the Hopi and Navajo. They also produced camouflage netting for the war, which many incarcerees were against. The question of whether or not, or how much, or in what ways, to support the war, was a source of divisiveness—between the Issei and Nisei, among family members and friends.

Joy did not remember the divisiveness or the camouflage or the irrigation system or the Native Americans. Her memories were only beginning. There was not yet the understanding of freedom against which she could place her memories of being a prisoner. She remembered dust. Cold winters. Eating bologna for dinner. At first there were no forks or spoons, only knives. She remembered playing with marbles and string. Even though the guards in the towers were very close, they had distant, nondescript faces, less expressive than the guns they were holding.

Joy’s father was a cook in the mess hall. Her mother worked in the elementary school. Poston was divided into three camps. Joy and her family were in Poston 3. Her aunt and uncle and cousin were in Poston 1. Joy asked her cousin, who was three years older, what she remembered, and if she would share what she remembered with me, and she responded with a list that would affirm the common expression among the youngest incarcerees: that being incarcerated—but that is not the word used to preface the sentiment—felt like summer camp: biking, swimming, playing Monopoly, kick the can, swimming in the river. Movies were screened outdoors once a week. The men caught snakes and made snake soup. The women carved wooden birds. Summer camp, and yet it was noted that the winters were cold. The memories were of friends and time and space, not yet struck through with the resentment, the anger, that would have upended the sense of peace that accompanied being a child in an exceptional place. To grow older often means to grow silent. As the children aged, the peace they felt and forced themselves to believe in, aged too. To Joy’s bologna, her cousin added: tongue, heart, liver, Vienna sausage, and okoge, the crust burned onto the bottom of the rice.

1942, 1943, 1944, 1945. It was not as difficult for Joy, she said, as it was for her parents. But it was even more difficult for them after incarceration, when her family was released and returned home to Los Angeles. The postwar atmosphere was even less kind. The veil of security separating the Japanese Americans from the multifarious expressions of white anxiety and rage had been lifted. They were welcomed home by anti-Japanese signs. Japanese houses were shot at. My great-aunt Joy was vilified by her classmates. Her mother was a maid for a white family in Beverly Hills. Joy remembers being fed the white family’s scraps. She remembers especially the fat from the white family’s meat.

The grant jury: A powerful new exploration of Japanese-American incarceration that speaks to our current cultural conversations about trauma and silence, reparations, and the carceral state. Brandon Shimoda is an elegant, incisive writer, and his book on the afterlife of the concentration camps will help to ensure that this dark stain on American history is never forgotten. As the eightieth anniversary of Executive Order 9066 looms, readers will be tremendously moved by the ambition and scope of his examination of the concepts of reparations, displacement, national belonging, and memory - and by the brilliant and painful insight regarding the limits of each that the book offers.

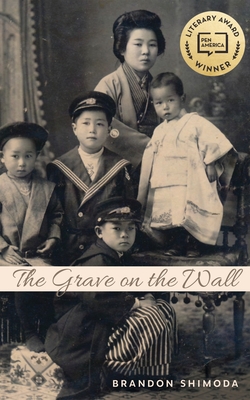

Brandon Shimoda is the author of seven books of poetry and prose, including The Grave on the Wall (City Lights), which received the PEN Open Book Award, and Evening Oracle (Letter Machine Editions), which received the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America. Recent writing has appeared in Harper's, The Nation, The Paris Review, and Tricycle, and he has given talks on Japanese-American incarceration at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, the University of Chicago, the University of Connecticut, the International Center of Photography, and elsewhere. He teaches at Occidental College and in the low-residency MFA program at Pacific Northwest College of Art, and works at the Pima Community College Library, in Tucson, Arizona.

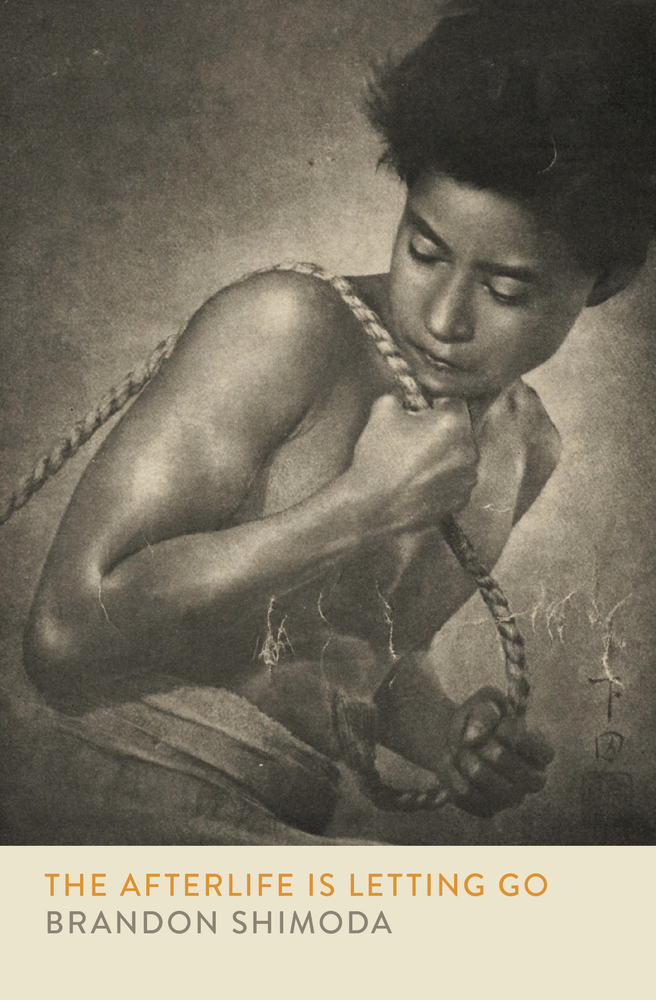

Selected Works