The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance

The project:

The Cost of Free Land investigates the parallel histories of the author's family, who fled anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia in the early 20th century to settle on land in South Dakota given to them by the U.S. government, and the Lakota who had been forced off that land, examining the question of what happens when the oppressed become the oppressors.

From The Cost of Free Land:

At their mother’s insistence, the four oldest Sinykin kids had all filed for their own free land. Enticed by the papers, railroad ads, and federal financial incentives, more than 100,000 newcomers, many of them immigrants, moved to western South Dakota between 1900 and 1915. My family, along with approximately thirty other Jews, homesteaded an area that locals today still refer to as Jew Flats.

By this time, the Sinykins and their neighbors had built the shacks required to prove to the government that they were in it for the long run and deserving of that free land. In the treeless plains, most settlers opted to build using cheap, thin plywood, hauled from faraway towns and lined with red or blue tarpaper. The light of kerosene lamps flickered through windows; cracks in the tarpaper glimmered “almost as thick as the stars,” recalled one neighbor. Built in a matter of days, these “houses'' were no more impressive than a packing box. And yet they must have been proud of these one-room homes, a serious promotion from a sod house.

By the time my family got to Jew Flats, more than seventy Jewish farm settlements, composed of anywhere from a few dozen to 2,500 people, had been established throughout the West, including California, Oregon, the Dakotas, Kansas, Minnesota, Colorado, and Utah.

This book, like all books, is a reflection of the time in which it is written; it speaks as much to the present as to the past. What is clear from this vantage is that the freedoms American society afforded to the Sinykins were denied to their Lakota neighbors.

Unlike their Lakota neighbors, the children of ghost dancers, who were being jailed for practicing their culture, the Jews of Jew Flats were free to worship how they liked. They had their mikvah. They had their own rabbi, Hyman Kozberg, Harry’s cousin, who was educated at the Slutsk Yeshiva and trained as a shochet, a Jewish butcher, able to kosher meat. He taught the children Hebrew and led services, using a Torah that they’d brought with them from Sioux City. “In the midst of the prairie, [Faige Etke] maintained her rigid piety and a kosher home,” Aunt Etta wrote in the family history in the 70s.

Unlike their Lakota neighbors, the Sinykins were free to educate their children however they wanted. They hired their non-Jewish neighbors, the Calloway siblings, to teach their kids and some of the adults in twin claim shacks a few miles from Harry and Faige Etkes. Unlike the segregated Indian schools, settlers mixed with non-Jews, boys and girls all together.

Unlike the Lakota, who weren’t able to farm or ranch collectively with their relatives because the Indian Agents, in their assimilationist drive, often doled out allotments far apart, the Sinykins and their cousins and friends survived by collective effort, unbothered by government interference.

Unlike most Lakota, who couldn’t get a bank account or handle their own money, the Jews of Jew Flats could and did leverage the worth of their land and their cattle for a mortgage or bank loan.

Later, Jack Sinykin will pose with White Bull, and other family members will take snaps at roadsides with people in traditional Dakota and Lakota dress; later, there will be rumors of bootlegging and of cousins who helped Lakota to bury their dead; but at this point, in the early 1900s, there’s no archival evidence that they knew their Lakota neighbors at all. The homesteaders, who had minimal interaction with the Lakota, had no idea how different their opportunities were from those of the people on the other side of the invisible wall that defined the reservation.

This was “evidence of a successful federal Indian policy,” explains historian Mikal Eckstrom, whose ancestry is both German and Nimiipuu, and who is one of the few American historians who has studied the relationship between Jews and Native Americans. By keeping these spaces separate, the Bureau of Indian Affairs believed it could more easily control Natives and, says Eckstrom, “keep settlers safe.”

Despite the fact that no one on Jew Flats or any of their white neighbors ever reported any Lakota attacks on white settlers, and in some cases the complete opposite was true, a culture of fear, created by the Buffalo Bill show, dime store novels, and early movies, thrived on the prairie and beyond.

The grant jury: A wide, deep, and ambitious book, one that peers inward at the heart of the country and its history of genocide at the same time it looks across the ocean. This is a brilliantly conceived family history, one that places questions of responsibility and atonement at the center of the conversation about America’s political future. Striking a balance among the overlapping issues of Indigenous rights, inherited responsibility, retribution, and healing is a complex task, but Rebecca Clarren approaches her project with candor and clarity.

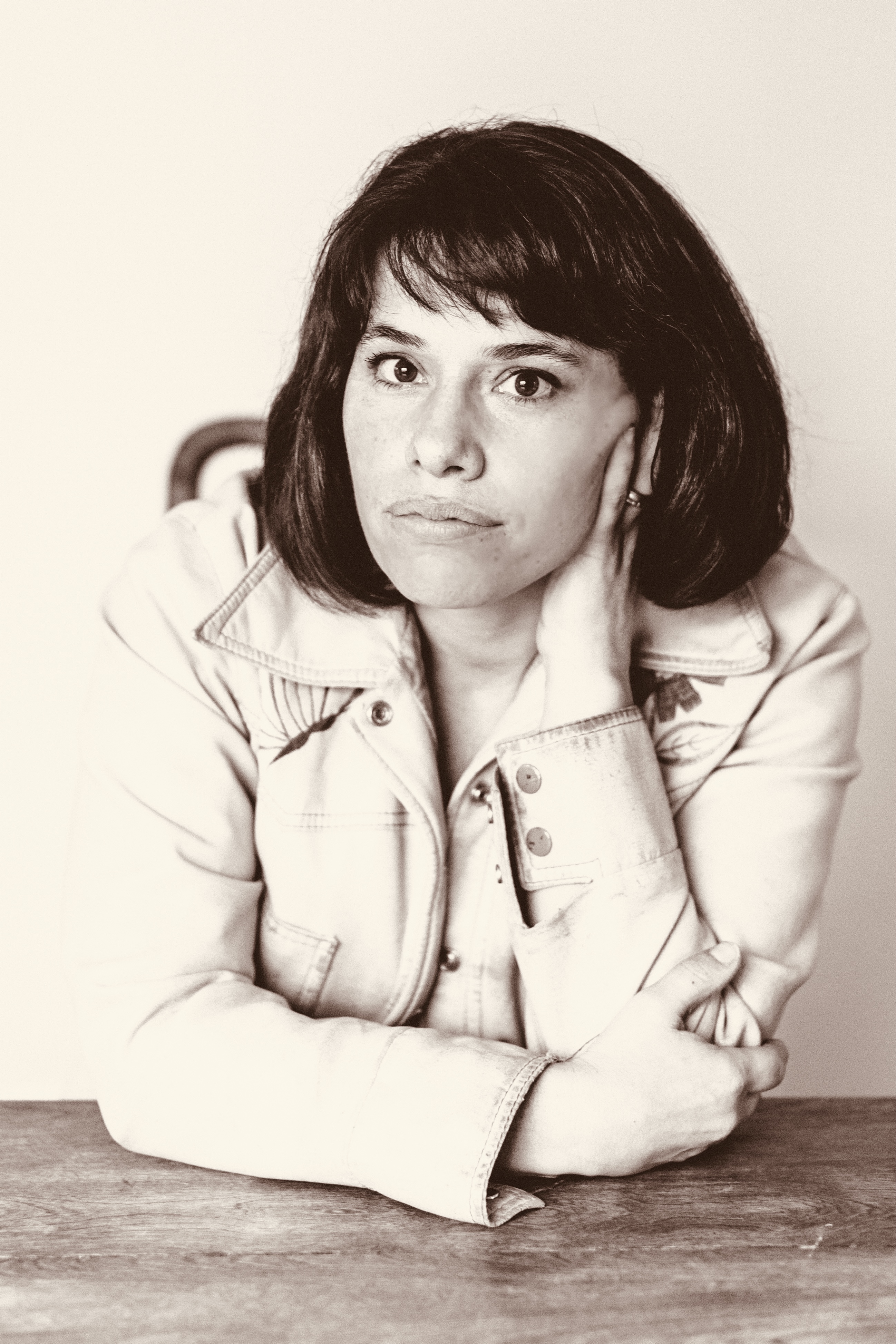

Rebecca Clarren has been reporting on the denizens and landscapes of the American West for more than twenty years. Her journalism, which is frequently supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism and has won a Hillman Prize and an Alicia Patterson Fellowship, has appeared in such magazines as The Nation, Indian Country Today, and High Country News. Her novel Kickdown (Sky Horse, 2018) was shortlisted for a PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction; The Washington Post called it “an impressive debut.”